My husband is a grief expert. Jeremiah doesn’t have a degree (yet), but his unfortunate life experience has taught him what it means to grieve and how to help people grieve. When Jeremiah was 15, his dad died suddenly due to an unexpected heart attack.

Jeremiah’s life following his dad’s death has felt painful, frustrating, and hopeless at times. However, his dad’s untimely passing also began a long process which transformed Jeremiah’s raw grief into refined healing. Each day is still hard in its own way.

“People like to promise that it’ll get easier, but dad being dead has never been easy. I think about dad every day. I have learned to hold the pain for a second and then let it go. I hold it, I acknowledge it, and then I just let it go.”

Reaching the acceptance stage, to him, does not necessarily mean knowing why a tragedy happened. He says, “I just have to take this and be a better person for it.” Now that Jeremiah has reached acceptance himself, he meets his grieving friends on a level of empathy and love. He and his beloved family have received condolences in many different shapes and forms. Jeremiah found some condolences to be helpful, and others to be potentially problematic.

The First Few Blurry Days

Jeremiah remembers, “I have very, very vague memories of the first few days, but I do remember the people who were consistent in following up after that.” The Savage family received an influx of visitors, and support, and love, and tissues, and casseroles, and hugs on those first few blurry days. But eventually, most people move on. Even close friends move on.

However, a family in their neighborhood who wasn’t exceptionally close to the Savage family before Karl died brought dinner every week for two years after his death. Jeremiah says gratefully, “They just stepped up and kept stepping up.” When Jeremiah’s friends grieve, he shows up as part of the initial influx of love and support. He shows up and he keeps showing up, a month and a year and two years later.

Remembering Important Days

Reach out and keep reaching out, even when a significant amount of time has passed. Jeremiah explained, “People remember for a year, and then you’re kind of on your own.” He and his family still needed support after a year passed, and they feel incredibly grateful to those who remembered them, and who continue to remember.

Even if we don’t make dinner for a grieving family every week for two years, there are other significant ways to remember and to reach out. Remembering important days, such as the late person’s birthday, wedding anniversary, and death anniversary can help the grieving family feel their important person is loved and remembered. Even now, Jeremiah still appreciates people reaching out and simply expressing their love on especially difficult days.

Problematic Condolences

Jeremiah recalls receiving some problematic condolences. Many condolences that other people would have found comforting upset him. Grief is an incredibly individualized process. As a caveat, Jeremiah states, “I have very strong opinions which are personal, and I don’t know if these are for everyone.” However, we can all learn what kind of support is generally helpful and unhelpful by virtue of Jeremiah’s experience.

Rushing or Slowing the Grieving Process

Being there with someone during every stage of the grieving process can be brutal, both for the griever and for the friend. It is also necessary. “Sometimes you just have to sit there with someone and not try to move them faster than they’re willing to go.”

A grieving person needs his or her time and space to grieve internally. Although friends can help with external things, such as making dinner, taking the kids, and cleaning the house, there is nothing a friend can really do to expedite the grieving process.

Just as harmful is slowing the grieving process. We can cover grief by never facilitating discussions about the person who has died, or by acting like the tragedy hadn’t happened. Jeremiah explains, “If people are covering over your grief, then you can’t go through the pain, which is necessary. As hard as it is to be with someone in each of those moments, you have to let someone move through each of those steps.” There is no possible way to skip them altogether.

Ignoring the grieving process does not make the grief go away. Rather, it keeps the person who has lost someone in one of the beginning stages of grief, such as denial or anger.

Explaining the Death

Another issue occurs when people offer reasons for why a person died. For example, many people told Jeremiah, “God needs your dad in the spirit world. He’s doing a big work out there.” This felt incredibly painful because, as a 15-year-old, his mind’s automatic response was, “I need my dad.” He felt this condolence implied that Jeremiah and his family didn’t need his dad. He also felt this comment blamed Karl’s death on God, which only made his struggles of faith more complex.

Jeremiah adds, “Part of the grieving process is acceptance, and people are going to come to acceptance in their own time and in their own way and I feel like trying to offer solutions to someone else’s grief is the wrong way to go about it.”

Imposing a Relationship

Many people experience complicated grief, which occurs when “feelings of loss are debilitating and don’t improve even after time passes.” Often, complicated grief can be intensified when person grieving is the survivor of an estranged parent. Seemingly harmless condolences such as, “I know your dad’s so proud of you,” “I know your dad’s watching out for you,” or “I know he’s here with us right now,” can be extremely damaging to a person experiencing complicated grief.

These comments can intensify grief because they impose a relationship that may or may not be a reality. A child of an abusive parent would not want to hear that his deceased parent is close. Although Jeremiah does not experience complicated grief, he still finds comments imposing a relationship hurtful.

These comments can intensify grief because they impose a relationship that may or may not be a reality. A child of an abusive parent would not want to hear that his deceased parent is close. Although Jeremiah does not experience complicated grief, he still finds comments imposing a relationship hurtful.

Jeremiah very rarely feels his dad’s spirit with him. When people who don’t know Jeremiah that well or didn’t know his dad very well claim that, “He is here with us now,” it makes him feel unsettled. Jeremiah advises, “Be careful about assuming things. Unless you are part of that relationship, you’ll never know the complete intricacies.”

However, Jeremiah understood that those offering condolences were genuinely trying their best to offer support in the way they knew how to. “If you’re ever worried about what to say to someone, just be earnest. Just say what you’re really thinking and feeling.” The intent matters more than the words do.

The Common Problem

The common issue with these forms of condolences is that, Jeremiah explains, “seeing someone hurt or grieving…makes us feel uncomfortable, and so we try to say things that make us feel good.” In an effort to diffuse our own feelings of discomfort, we inadvertently hurt those who are grieving instead of helping them. Rather than worrying about saying the right thing, we can focus instead on three things: expressing love, providing support, and offering help.

Express Love

It is enough to express love for the person grieving, express love for the person who has passed, and to leave comments at that. There are innumerable ways to express love; however, being empathetic is the heart of all expressions of love. Expressing love often begins with acknowledging how hard your grieving friend’s circumstance is.

Brené Brown eloquently states, “Rarely can a response make something better. What makes something better is connection.” This animated short of Brown’s talk shares what it means to respond with empathy rather than with sympathy.

Although responding with empathy is more uncomfortable for us, we will to better for our friends and for ourselves if we allow ourselves to be vulnerable enough to feel sad with our grieving friends. “Just acknowledge this is really hard for you, and for me.”

Provide Support

The best friends usually say the least. After expressing love and acknowledging a friend’s hardship, listening with empathy naturally follows. “The best way to draw out good things from someone sometimes is to just let them talk and just be there as an emotional, a physical, but not an audible presence.”

The best friends usually say the least. After expressing love and acknowledging a friend’s hardship, listening with empathy naturally follows. “The best way to draw out good things from someone sometimes is to just let them talk and just be there as an emotional, a physical, but not an audible presence.”

Like expressing love, providing support can also take many different forms. Providing support can translate into praying and fasting for a grieving friend (which is different than saying “I’m praying for you!”). Providing support can mean re-introducing art, movies, and other things your friend loved before their loved one passed away. Friends can keep their friends from losing everything they loved when they lost what they love most.

Offer Help

Finally, offering help can alleviate strain and help a grieving person know they can count on you. The key in this step is offering. We can give love and support freely, according to our terms. Ultimately, however, the person in grief decides if he or she will accept help. For example, Jeremiah always offers his phone number to his grieving friend and says, “If you’re ever having a breakdown and need to call to someone, I’m right here.” The person may never call, but the point is that they know they have the option to call.

Other ways to offer help are to offer to clean, bring dinner, and watch the kids. These recurring tasks may seem small to us, but they could feel daunting and even unbearable to friends fresh in their grief. It’s important to offer before doing, also, because different tasks have different nuanced meanings to grieving people.

Other ways to offer help are to offer to clean, bring dinner, and watch the kids. These recurring tasks may seem small to us, but they could feel daunting and even unbearable to friends fresh in their grief. It’s important to offer before doing, also, because different tasks have different nuanced meanings to grieving people.

Therapist Megan Devine offers this advice, “That empty soda bottle beside the couch may look like trash, but may have been left there by their husband just the other day. The dirty laundry may be the last thing that smells like her. Do you see where I’m going here? Tiny little normal things become precious. Ask first.” Only the person in grief knows what things are important and what things aren’t significant.

Once again, no matter what you choose to say or how you choose to help, “The important thing is the intention behind what you’re saying, and the fact that you’re consistent and keep checking in. No matter what, no matter if your first attempt is awkward and bungled, it’s so important that you go back and continue to offer support” (Jeremiah).

These Clearer, Current Days

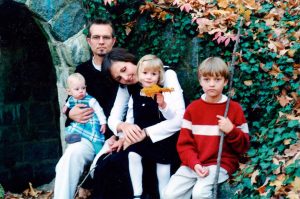

I may be biased (because I just married into this family), but I’m willing to bet the Savages are the most empathetic, loving, and long-suffering people. I didn’t know them before Karl died. But I do know they have been refined and shaped by their grief. Even though their favorite guy was taken away from them, they still love wholeheartedly and completely. They are still a complete family of 5, and they still welcome newcomers like me to their circle without hesitation.

They are fearless. They don’t close their hearts to love out of fear or lingering hurt. Since Karl’s death, both Jeremiah and his mom, Julie, have felt directed to become therapists. They are willing to relive and remember their toughest experience so that they can benefit others. They are willing to empathize. They are willing to mourn with those who mourn, and grieve with those who grieve. The Savages are grief experts. They express love, provide support, and offer help. Each of us can do the same.