Like the the dark of a child’s closet, the deep-end of the pool, and the space beneath our beds just big enough for a person to hide, Carol Lynn Pearson’s “The Ghost of Eternal Polygamy” (GEP) preys on our innate fear of the unknown.

I’m not going to lie and say the idea of eternal polygamy doesn’t frighten me. I remember the first time it came up in conversation, driving with my brother and his now fiancée, as he talked about the shortage of worthy men in the Church. “I’ll take on another wife if I have to in the celestial kingdom,” he said with the dutiful air that typifies his personality as a whole.

Unlike my brother, I am not blessed with an unwavering sense of religious duty.

So, this led to an argument between us about the sanctity of marriage and, if everyone is going to get to be sealed in heaven… is an earthly sealing even meaningful? My brother held that polygamy is a celestial law, and it would be required of us in heaven.

The more I argued, the more fearful I became that whoever I selected for my spouse in this life, I would have to share in the next. The idea made me sick.

I prayed, read my scriptures, and combed through the church-approved and the scholarly until I personally felt satisfied: exaltation does not require polygamy.

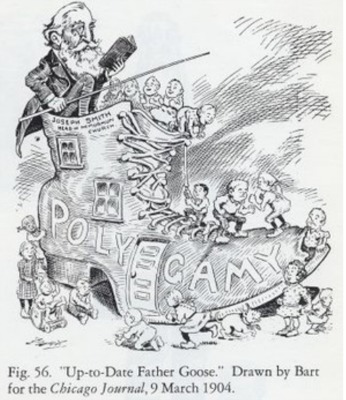

Brian C. Hales, curator of Joseph Smith’s Polygamy and author of Modern Polygamy and Mormon Fundamentalism, has devoted the better part of his time to sorting through the nitty-gritty facts of Mormon polygamy. In his recent review of Pearson’s book, Hales addresses GEP’s shortcomings.

Casual Research Kills Facts

Pearson’s book is not entirely without base; at least four of the points she lists are founded:

- The history of the establishment of polygamy by Joseph Smith is messy.

- Earthly polygamy is unfair to women.

- Widows who have been sealed to their deceased husbands are treated differently than widowers who were sealed to their deceased wives.

- Cancellations of sealings have not always paralleled individual desires or legal marital decrees.

But, as she attempts to prove each of these points, casual research and a modern view riddle her passages with historical inaccuracies.

For example, GEP calls out the messiness of earthly polygamy: a valid point. But, instead supporting this argument with fact, the GEP relies on pieces of evidence like this:

“Numerous young women (and some older women) were approached by Joseph and promised the highest exaltation in heaven — along with their entire family — if they accepted him as their husband and were ‘sealed’ to him for eternity” (55).

According Hales, this point is completely false. Pearson’s writing also suffers from presentism, as she makes assumptions about how the women of the time would have felt about polygamy based off our own modern views of the practice.

this point is completely false. Pearson’s writing also suffers from presentism, as she makes assumptions about how the women of the time would have felt about polygamy based off our own modern views of the practice.

After all this faulty reasoning, GEP then asserts that Joseph Smith was in error: “plural marriage never was — is not now — and never will be ordained of God” (21) and that it constitutes “extraordinary spiritual abuse” (22); a conclusion she came to without the help of standard works or canonized material.

Ethos, Pathos, and Ethos Again

If Pearson had stuck to her previous four claims, we’d be left with an empty argument — founded, but ill-researched. However, she doesn’t stop there.

Instead, Pearson goes on to make three additional, unfounded claims:

- Polygamy is required in the celestial kingdom.

- Child-to-parent sealings will be unfair in eternity.

- Eternal polygamy is unfair to women.

These three points constitute the bulk of Pearson’s discussion.

Hales points out the uniting concept of “eternity” within each point; an assumption Pearson has no authority to make. Revelation has yet to address how polygamy will work in the eternities.

Pearson also demonstrates a limited understanding of child-to-parent sealings:

“Children who are born into a marriage between a sealed widow and a new husband, though these children are raised by their biological father, are understood to be destined to live eternally in the spiritual kingdom of a man they have never known” (96; see also 8).

GEP provides no source for these “understood” doctrines, nor does she elaborate on what she means by “spiritual kingdom.” Presumably, the GEP is assuming that each household will then constitute an individual kingdom in heaven — which is frankly false doctrine.

We are taught from a young age that each of us is a divine son or daughter of our eternal parents. When we are sealed, we are united together under this eternal parentage. Exactly how the individual sealings will affect us has yet to be revealed, but the GEP offers an explanation that creates unnecessary fear and confusion.

Throughout the book the GEP uses unconventional sources to hold up its arguments: imaginary conversations, portions of Pearson’s diary, her own poetry, and multiple expressive, fictional accounts. The final chapter is a really long “what if…” scenario composed by the author.

The book also pulls much of its data — and an entire section titled “other voices” — from a survey released by Pearson on social media. Only 43% of survey participants were active, covenant-keeping Latter-day Saints. Respondents were given the opportunity to share their own personal experiences with polygamy. “85 percent of the stories expressed sadness, confusion, [and] pain” (10), according to Pearson.

GEP makes hardy use of these narratives, interspersing 126 of them throughout the book for emphasis. Using biased, present-day accounts to make an argument about an abandoned practice is hardly convincing on its own. But GEP uses a shroud of emotion, dressed up in Pearson’s eloquent prose to affect its audience.

The Truth Is We Don’t Know

“Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him” (1 Corinthians 2:9).

The Church hasn’t said much on plural marriage since 1890, leaving a void to be filled with false information from unauthorized sources. This is why Pearson’s book is particularly dangerous.

I’m sure there are many confused members out there, just like me, who would love a solid answer on the topic. Heck, Church history would be one-hundred times easier to swallow if we just dismissed polygamy as human error. But it wasn’t.

Abolished over a century ago, polygamy exists today as a religious hurdle — a test of faith. Members must do their best to reconcile any hard feelings the Church’s polygamous-past may elicit. Difficult as it may be, it only gets harder when you’re getting your information from ignorant sources.

Thankfully, Pearson isn’t the only woman writing about Mormon polygamy.

Presentism Be Darned

Pulitzer Prize winner, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, is a scholar through and through. Best known for her critically acclaimed snapshot into the daily life of a 18th Century midwife, “A Midwife’s Tale,” Ulrich’s primary-source approach to examining history gives her writing historical accuracy, with a touch of creativity and a novelistic feel.

In her latest book, “A House Full of Females” (HFF), Ulrich provides an intimate exploration into the lives of the early Mormon women and their struggles with polygamy. While GEP leans on elegant prose and emotional response to build a case, HFF constructs from the ground up using information pulled directly from the diaries and minutes of women at that time.

Ulrich takes special care to provide intimate background details, constructing the story from the ground up with reliably sourced information. HFF’s primary source approach means the reader isn’t cheated out of historical accuracy for the sake of an emotional reaction.

Unlike Pearson, Ulrich doesn’t write in hopes of upholding our modern sentiments, but writes with her vision planted firmly in the past. She never passes judgment on the actions of the figures she’s writing about, she never infuses her own opinions or explanations into their lives, and she absolutely does not push her agenda using modern poetry and surveys. In fact, Ulrich does not have an agenda to push.

How could women simultaneously support a national campaign for political and economic rights while defending marital practices that to most people seemed relentlessly patriarchal?

Ulrich asks this question at the beginning of her book, and spends the next 15 chapters fleshing out the complicated relationship between 19th century LDS women and polygamy, without shying away from the ugly or over-glorifying the good. Ulrich provides the accounts of women in their own voices, and let’s them answer this question on their own.

If the Church’s history of polygamy is troubling you, do your research, seek the truth, study it out. But if you’re only going to read one book about it, let it be “A House Full of Females.” And remember, Ulrich’s account of worldly polygamy is just that: an account of worldly polygamy. In no way does it reflect the handling of polygamy in the eternities.