I’m not going to pretend that the entirety of what you’re about to read is true. It may very well just be a fun story for Cub Scouts to talk about around the campfire, but there’s something inside me that hopes it’s real. But this isn’t about my opinion (though I will include it), this is about the legend. The story of lost gold and how it supposedly ended up in the hands of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints well over one hundred years ago.

A little context

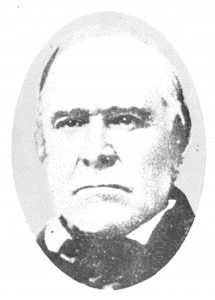

According to the Deseret News, Thomas Rhoades (also spelled Rhoads) joined the LDS Church in 1835. In 1846, he set out with a few others to scout the path Mormon pioneers would travel the following year on their trek to Utah. He overshot Utah valley by just a smidgen and ended up in California, where he worked for a gold miner named John Sutter (coincidentally the man who sparked the California Gold Rush when the precious metal showed up at his mill).

Once Brigham Young determined that Utah valley was “the right place,” Rhoades backtracked from California to the Saints’ new home.

This is where things get interesting

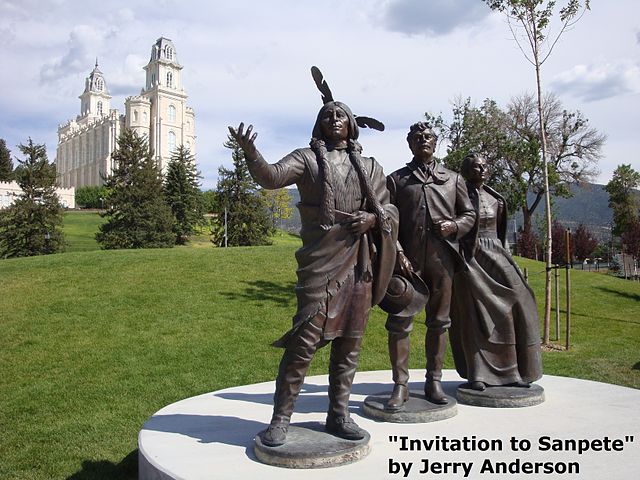

As legend has it, Ute War Chief Wakara (also called Chief Walker) was baptized into the Church and told Brigham Young of a sacred gold mine in the Uintah Mountains that could help the Church with their financial struggles. Western historian George Thompson says the Utes called the mining land “Carre Shin Ob,” meaning, “there dwells the Great Spirit.”

The Chief and President Young came to an agreement: Only one white man could know where the mine was. On each trip to the mine that man could only take what he could carry back with him, always under Ute supervision. Finally, only the Mormon Church had permission to use the gold.

The pair agreed on Thomas Rhoades (circa 1852), who conveniently spoke Ute. A Ute escort led Rhoades to the mine. Each journey is rumored to have taken about two weeks. As time went on, Rhoades discovered even more gold mines, totaling seven.

Rhoades family records allegedly indicate that the Salt Lake Temple’s Angel Moroni and some structures within the temple are coated in gold leaf from the Rhoades mines.

How did the gold get there in the first place?

Some gold was said to be left by Spanish entrepreneurs who forced the Native Americans to dig some of the mines for them. But, for whatever reason, the Spanish were unable to transport the gold out of the mountain range. Some believe that the Spanish Escalante/Dominguez expedition of 1776, which led the explorers through the Uintah Basin, was an attempt to recover the gold. If that was the case, they were apparently unable to find it.

How much gold are we talkin’?

Thomas Rhoades, and later his son, Caleb, are said to have taken gold from the mine for over 50 years. The very first haul is said to have weighed a little over 60 pounds. Once Chief Walker died, the following chief, Arapeen, continued to allow Caleb to take from the mine. Arapeen’s successor had different ideas. He banned Caleb or any successors from gathering any more gold.

Caleb appealed to the U.S. government. He wanted the government to lease him the land. In return, Caleb promised to pay off the national debt. The government denied his request, but the attempt gives us a small hint as to how much wealth the mine still housed.

So, what happened to it?

As far as we know, Caleb Rhoades took the secret to his grave. Brigham Young never spoke of the gold. Some speculate it never existed in the first place. Others speculate it’s still there, waiting for someone to discover it.

Some people believe the Church is in possession of a map that leads back to the mines. They speculate the Church may be keeping it locked away in their own mine-like Granite Mountain Records Vault.

Still other believe the mines are protected by spirits, and that going near them may end badly. Indeed, at least two people have died while looking for the mines. In 1986, one person died in a dynamite blast. Another man, a descendant of Thomas and Caleb Rhoades, died of a heart attack while searching for the mines.

An interview with a local expert

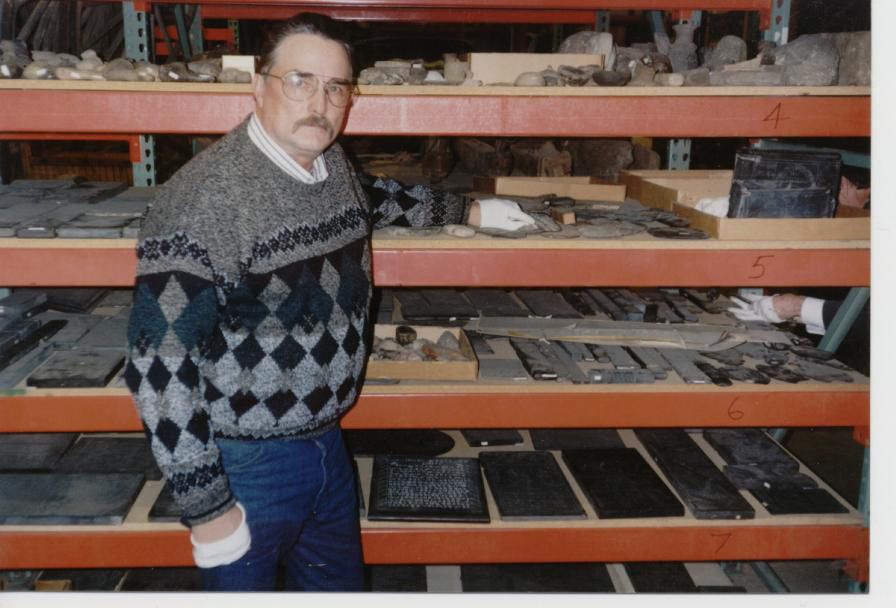

Author and Utah treasure lore expert Steve “Doc” Shaffer wrote the book when it comes to the lost Rhoades mines, literally. It’s called “Out of the Dust: Utah’s Lost Mines and Treasures” and you can buy it on Amazon. He’s personally worked with members of the Rhoades family to find the mines, and he’ll be groaning through this whole article because his research tells a slightly different story than the legend.

“People think [the Rhoades mine] is a fake, but I’ll attest that it’s not. I was with the family long enough to know the difference. I’ve seen the maps and seen the evidence . . . I don’t care what people think,” he said.

He explained that the Utes permitted Thomas and later Caleb to take from two mines. Thomas took from a mine that Shaffer says is located “up by Moon Lake” in the Uintahs. He says the other mine is (notice the present tense there) located on a Ute reservation. He gave me an even more specific location, but asked me not to reveal it in this article.

“I was taken by one of the old Utes and we went into an area—I was well trusted because when I was younger they used to take me places and show me Spanish mines . . . And as I was walking to this area they had me stop and turn around and there was a bear in the tree—carved in the tree—and that bear was to protect that mine.

“And so we went down into this little gully and they pointed and I looked and didn’t see anything for a minute, and then I could see these rocks stacked into this mouth-looking tunnel, and they said, ‘That’s the lost Rhoades mine. Now you know.'”

But Shaffer hasn’t personally seen inside the mine. He respects the sacred nature of the mine and wouldn’t betray the trust of those who revealed its location to him. “I made a promise I wouldn’t,” he said.

He specified that the reservation mine was not of Spanish origin. It was a sacred mine kept secret by the Native Americans. It wasn’t filled with treasure in the Pirates of the Caribbean sense, but rather Shaffer says that Caleb described the rock within the mine as “rotten with gold.”

Shaffer confirmed that gold from these two mines did indeed go to the Church, but Caleb secretly took from five other mines for his own purposes.

“I know the story to be true,” he said.

What is the truth?

Before speaking with Shaffer, I had some serious doubts about the validity of this legend. But after an interview with a first-hand witness attesting to its existence, I’m ready to count myself as a believer.

Sure some of the details of the legend are definitely a little wild and have undoubtedly been corrupted over time, but I believe there really are lost mines in the Uintah mountains that may house some impressive artifacts and/or vast amounts of gold. I believe Thomas and Caleb Rhoades took from some of those mines to financially help out The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

It’s fun to believe it. It’s fun to think that an ordinary hike could turn into an Indiana Jones-worthy adventure. Maybe that’s why people still look for the Rhoades mines. Maybe that’s enough to get you out there looking too.